Sound & Space

Didakis, S. (2007) “A Framework for Interactive Sonic Design into Architectural Spaces”, Chapter 2, Master Thesis, Belfast, 2007

Sound and space are inextricably connected as each one performs the other ‘bringing aurality into spatiality and space into aural definition’ (LaBelle, 2002). Spaces redefine and shape the acoustic attributes of sound, although this shaping can also work the other way around, as the ‘poetically expressed’ space can transform experience and perception. This symbiosis needs to be approached in an efficient and creative way so that new conceptual proximities and functions will emerge. The relation has to demonstrate conversational events between space and aural perception and needs to redefine architectural form-making as a process of amplified expression.

The invention of the telephone in 1876 by Alexander Graham Bell and the invention of the gramophone in 1877 by Thomas Edison created a new state of awareness and a ‘formation of [a] modern sound consciousness’ (Thompson, 2004). The displacement of sound in time and space was now possible, as the ethereal nature of sound could be captured, transformed and manipulated through electric circuits and wires. The acoustic energy was liberated from the past and the present, and could live in a distant time and place. A few decades later, artists and engineers begin to see the power of these new media, and start experimentations on the ways these devices can alter our perception and consequently our lives.

Christine Kozlov explores the relation between time, space and sound with the installation ‘Information: No Theory’ in 1970. In this work, tape loop recordings are used to combine sound and space in a social context, and to create an environment where the sounds of the near past are heard in the present, and same time the sounds of the present are recorded and played in the future. This sonic environment creates a time-defined anticipation between the participants, the architectural space, and the acoustic events. The recording technology becomes an important aspect of the actual event itself, and as Baudrillard observes: ‘the very definition of the real is that of which it is possible to give an equivalent reproduction’ (Baudrillard, 1983).

Alvin Lucier in the same year investigates the way technology can be used to redefine the physical relation of sound and space with his work ‘I am sitting in a room’ (Lucier, 1990). The piece is performed with the composer sitting inside a room where he speaks a text while his voice is recorded on tape. The recorded passage is played back again in the room and then re-recorded again a number of times. During every process, the room resonances and the electric distortion creates a shape alteration to the sound, which results into a conversational interaction between the spatial acoustic attributes of the room, the sound source, and the recording medium.

As it becomes apparent, hearing attentively sounds in space one can detect the shaping process between this interaction and the inheritance of the physical characteristics of the room into the reverberant properties of the sound. Stuart Jones argues that ‘this dynamic sound-event-space relationship means that although one may see space as an object, one other may hear it as activity’ (Jones, 2006), and consequently this relationship needs to define a semantic vocabulary for the communication between sound and space.

Aural Awareness

‘Buildings are never silent, nor they have ever been. The crash of the portcullis, and the chains of the drawbridge in castles, the creaking of cottage shutters, the quiver of air-conditioning, the glissandi of outside lifts suspended from facades, etc.’ (Delage, 2002).

This passage describes the way Bernard Delage experiences and perceives aural awareness; that is the conscious understanding of the acoustic environment of the spaces we occupy. Each space has the attribute to physically contribute to the shaping of the sound characteristics and create sonic events such as enveloping reverberation, amplitude alteration, resonance, and localization cues. To hear a space involves the active listening process in order to understand how buildings form their sounding environment, and as Rasmussen agrees, important information of the space can be derived from the radiation of the sound waves that exist within (Rasmussen, 1959). This information may involve spatial arrangement and organization, physical material and substance, symbols of culture and authority, as also artistic, technological, social, and historical contexts.

Unfortunately the average listener may find difficulties to aurally perceive the architectural space or identify all the subtle characteristics of the acoustic environment (Reed, 2000), as this process involves attentive and focused listening. However, the acoustic energy of an environment has the power to influence ‘both directly and indirectly the mood and emotion of those who occupy or live within a space’ (Blesser & Salter, 2007). For this reason sound may create better conditions between buildings and people, in order to craft an aural awareness that is more effective and responsive.

Such an example is the Cylindre Sonore, a physical construction designed by Bernard Leitner, and situated in the Parc de la Villette, in Paris. The intention of this space is to redirect and highlight natural sounds with electro-acoustic means, and to enable aural awareness and excitation to the visitors in such a way that their experience and perception are enhanced. Cylindre Sonore presents an architectural concept where sound is treated as an important ingredient, and ‘its ‘spatial boundaries have relevance only as they unfold, transform, or superimpose the experience of sound’ (Martin, 1994).

This proposes a way to transform the acoustic potential ‘through the structural, formal, and material characteristics of the architectural design’ (Dorsey, 2002), and also demonstrates a way for the sonic elements to become ‘a building material in the creation of space’ (Martin, 1994). Moreover, this collaboration has the power to effectively communicate meaning to the listener, and transform the listening process into something surprising and unexpected.

Sound Art

A form of art that considers sound as a medium to convey meaning and information such as poetic or artistic perspectives on a space is sound art. The practice of this art form is mainly focused in the way acoustics and psychoacoustics creates alternative experiences of the sonic environment. A necessity to define ways for the transformation of the aesthetic, functional, or artistic aspects of a space has driven many artists such as Max Neuhaus and Bill Fontana to investigate the integration of music and sonic design into public spaces and architectural buildings. Neuhaus has made numerous ‘sound installations’ (a term he originally invented) at the Times Square (New York: 1977-1992), the Museum of Contemporary Art (Chicago: 1979- 1989), the Whitney Museum of American Art (New York: 1983), and in many other sites as well. Neuhaus is mostly interested in the ‘design [of] sounds to fit spaces’ (LaBarbara, 1977), and also he is concerned and fascinated with the construction of sonic material and distribution into space, either physical or virtual, in order to communicate information, increase aural awareness, and alter memory and spatial perception (Neuhaus, 1994; Neuhaus, 1995). The majority of Neuhaus’ works try to create a space where sound needs to be discovered, and also to expand the range of sound possibilities that may occur in a space.

Bill Fontana takes a slightly different approach into his projects, as he uses environmental sounds from a specific site and transmits them into another distant location in order to evoke memory and visual imagery. Rudi (Rudi, 2005) describes Fontana’s work as a way to re-contextualize the sonic environment by this masking phenomenon of the naturally occurring sounds. The sonic worlds that are projected, attempt to create a new awareness of the acoustic environment and furthermore to remind the power of sound. One example is the Sound Island, an installation developed in the Arc de Triomphe (Paris: 1994), where sounds transmitted from the Normandy coast were projected into the monument with the use of loudspeakers (Fontana, 1996). This articulation of a new sonic space creates an unimaginable and ‘unexpected sense of place, time, memory and dimension’ (Fontana, 1996). Moreover, the placing of sonic material to where it does not belong or expected, is able to affect perception, listening and experiencing, and thus create a context in which sound is impossible to ignore.

The implications of these sound-works contribute to a state of aural awareness, and for a case where sound becomes an important medium to the distribution of information between the space and the listener. Alternative approaches to the relationship between sound and space have been also considered from composers that try to explore how perception about a space can be altered with the use of musical or sonic material.

Composing for Spaces

Among the first pioneer composers that forecasted the significance of the sound-space relation, was Edgard Varese (1883-1965). Varese, who originally coined the term ‘organization of sound’, was mostly interested in the ways that sound can be projected through time and space. His electronic music composition Poem Electronique was presented at the Expo ’58, and was specifically created for the Phillips Pavilion exhibition hall, a modern art architecture designed from Le Corbusier (1887-1665), and Iannnis Xenakis (1922-2001). The result of the installation was ‘a prototype of a spatial art where the architecture, color, images, voices, and music, were all superimposed to create an experience far greater than the components’ (Blesser & Salter, 2007).

An important consideration for the construction of the system was to create sound motion around the listeners and enable sound distribution and rearrangement through space (Tak, 1958). The effectiveness of the system was quite remarkable, and the result was the literal projection of music into space.

Another approach to the musical design of spaces has been considered by Brian Eno with his installation ‘Music for Airports’ (Eno, 1978). The sound articulation of this work involved artistic and poetic reflections concerning the relation of the context with people’s experiences, and also with the functionality and the communicational character of the space (Eno, 1996). The vision of the artist was not only to create ‘frozen’ music as in the case of Muzak, but in addition to construct a sonic environment that connects physical and virtual boundaries, and to provide a state of relaxation and contemplation to the travelers or the occupants of the airport.

The installations that have been applied to these spaces have variable functions and contexts, and try to endow architecture with the employment of spatial layers crafted through the use of sound. A meaningful interpolation between sound design and architecture needs to occur so that both are experienced as one coherent medium that can improve the quality of life and enhance our wellbeing. Sonic and spatial relations need to be considered in the architectural design, and ‘architecture would have to rethink itself: not as a resonant chamber or concert hall, but as a kind of sonic vehicle’ (LaBelle, 2002).

Interactive Trends

‘Even the most seemingly alienating of technological forms can soon become absorbed within our symbolic horizons, such that no longer appear alienating’ (Leach, 2002).

Architecture is the art and science of the design, arrangement and manipulation of the physical properties of space, and important consideration to this practice is to offer functional descriptions with aesthetic sensibilities. Sound can co-exist with this consideration, and has the power to create dynamic conditions for the reconfiguration of the space according to the human needs. Recent trends in architectural practice are involved with the use of new tectonic materials, sensor interfaces, and other dynamic systems that morph the architectural space ‘into an organism capable of conveying message using various media, integrating them into the building fabric’ (Puglisi, 1999). As a result transparency and interaction is achieved, and the structure becomes able to ‘flex like the muscles in the body, minimizing the mass, shifting the forces with the help of a nervous system based on electronic impulses, sensing environmental change, and recording individual requirements’ (Rodgers, R., cited in Puglisi, 1999).

These transformations introduce new dimensions of thought, and spatial, sound, and light conditions are characteristic elements that can be tuned accordingly to alter physical or ethereal substances, giving the opportunity to construct shifting processes for the attainment of desired inhabitancy. Several approaches have been considered to facilitate buildings that serve people – and not the other way around – providing even more sensitive interactive utilities that ‘will prolong our sense of freedom and possibility’ (Rushkoff, 2002).

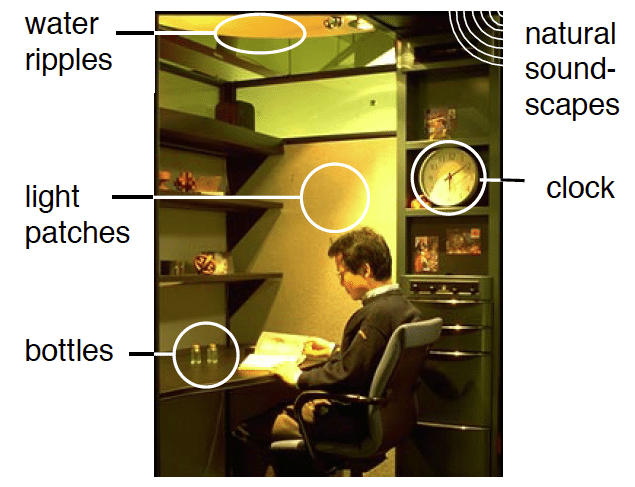

An approach to the design of interactive architecture has been taken from the MIT Media Laboratory that created the ambientROOM (Ishii et al, 1998). The space becomes a computer interface able to receive and transmit information with the use of sensors and physical objects that exist in the space. Sound is an important ingredient in this development, as it becomes a path for bi-directional communication, and also a provider of relaxation with the use of natural soundscapes played through loudspeakers.

The construction of specific sonic ambiences that are incorporated into the environment with the use of the digital technology is a way to redefine the identity of a space with great flexibility and adjust to a more responsive and effective lifestyle. An intersection between sound, architecture and interactivity, has been created in the Medical School Library at Queen Mary University, in London (Scott, 2004). The Ambiguous Object is a massive pendulum suspended from the centre of the oculus in the roof of the building, and its movement together with the sound emitted through space, create interactive elements for the composition of sound. This installation becomes a way to see architecture in a different perspective although the context of the space remains undisturbed and uninterrupted, and at the same time the sonic information can ‘be interesting and enriching to those who like to listen to it actively’ (Scott, 2004).

Another work that has similar characteristics and combines architectural structure with interactive sound composition and sensor technology is the Son-O-House developed by NOX architects and sound artist Edwin van der Heide (NOX, 2004; van der Heide, 2004). The eccentric metallic structure of the space intends to attract visitors to experience the sonic environment that is synthesized in real-time, creating sonic areas of interference that depend on the amount of movement that is tracked inside the space.

This allows a person to ‘not just hear sound in a musical structure, but also [to utilize the architecture and its functions] as an instrument, score and studio at the same time’ (NOX, 2004). The information that is tracked from the physical world is statistically analyzed, and rules and conditions define the way sound is generated and distributed. The installation intends to provide a space for relaxation, and additionally to create a collision between architecture, sound, physical presence and movement.

The following example is an interdisciplinary project that investigates the implications of brain-like technologies in correspondence to social behavior, architecture, and immersive multimedia environments. Ada (Delbruck et al. 2003; Eng et al. 2002) is an ‘intelligent’ room presented as an interactive installation for public entertainment. Multi-modal sensors receive visual, audio, and tactile information from the participants, and the system uses brain-like processes to evaluate the results and present emotional states (Eng et al., 2002). Roboser (Wassermann et al. 2003) is a musical system that the room employs to express itself musically, and the program gives the ability for the synthesis of musical material in real-time creating a 12-voice behavioral mode soundscape.

A space that integrates a ‘high level of behavioral integration and time-varying and adaptive functionality’ (Bullivant, 2005) as in this case, defines the way a person feels and reacts inside this setting. It is a fact that ‘by means of the mimetic impulse the living being equates himself with objects in his surroundings’ (Adorno, 1997), and this mimesis ‘dictates that we are constantly assimilating to the built environment’ (Leach, 2002). New approaches that ‘register fluidity’ (Goulthorpe, 2002) may be introduced as in the aforementioned examples that consider not only the spatial boundaries but also ‘the nature and quality of their interaction with the sounds surrounding them’ (Dorsey, 2002). This relation between sound, architecture and technology, becomes a case of exploration using imagination and creative contextualization.

The architectural space has the power to become an expressive art form that escapes normal functions, and communicates information inside a social context. The sonic adornments are a valuable consideration for the enhancement of the artistic and aesthetic properties of the space as they can create pleasant or reflective moods, and moreover they have the ability to personalize the space by producing attributes that give richness and texture to the architecture. Sound designers have to develop the desired sonic elements according to the concepts and the vocabulary of the culture that is involved in each particular framework, so that artistic and social coherence may be obtained.

References

- Adorno, T. 1997, ‘Functionalism Today’, in Rethinking Architecture, ed. N. Leach, Routledge, London, p.10.

- Bachelard, G. 1994, The Poetics of Space, Beacon Press, Boston.

- Baudrillard, J. 1983, Simulations, trans. P. Foss, P. Patton, P. Beitchman, Semiotext(e), New York.

- Blesser, B. & Salter, L. R. 2007, Spaces Speak, Are you Listening? Experiencing Aural Architecture, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

- Bullivant, L. 2005 ‘Ada: the Intelligent Room’, in 4D-Space: Interactive Architecture, ed. L. Bullivant, Wiley-Academy, West Sussex, p. 86-89.

- Delage, B. 2002, ‘Sound in Architecture’, Earshot, vol. 3, pp. 10-11.

- Delbrück, T., Eng, K., Bäbler, A., Bernardet, U., Blanchard, M., Briska, A., Costa, M., Douglas, R., Hepp, K., Klein, D., Manzolli, J., Mintz, M., Roth, F., Rutishauser, U., Wassermann, K., Wittmann, A., Whatley, A. M., Wyss R., & Verschure, P.F.M.J. 2003, ‘Ada: a Playful Interactive Space’, Interact 2003, Ninth IFIP TC13 International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction INTERACT’03, Sept 1-5, Zurich, Switzerland, pp. 989-992.

- Dorsey, T. 2002, ‘Revealing the continuum: an Investigation of Sound and Space’, Earshot, vol. 3, pp.12-15.

- Eng, K., Baebler, A., Bernadet, U., Blanchard, M., Briska, A., Conradt, J., Costa, M., Delbruck, T., Douglas, R., Hepp, K., Klein, D., Manzolli, J., Mintz, M., Netter, T., Roth, F., Rutishauser, U., Wassermann, K., Whatley, A., Wittmann, A., Wyss, R., and Verschure, P. 2002, ‘Ada: Constructing a Synthetic Organism’, Proceedings of the 2002 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Lausanne, Switzerland.

- Eno, B. 1978, Music for Airports, Editions Eg Records, UK.

- Fontana, B. 1996, ‘Borrowed Soundscapes: the Sound Sculptures of Bill Fontana (1973-1996)’, Available at: http://www.resoundings.org

- Jones, S. 2006, ‘space-dis-place: How Sound and Interactivity Can Reconfigure Our Apprehension of Space’, Leonardo Music Journal, vol. 16, pp. 20-27.

- Ishii, H., Wisneski, C., Brave, S., Dahley, A., Gorbet, M., Ullmer, B., & Yarin, P. 1998, ‘ambientROOM: Integrating Ambient Media with Architectural Space’, Conference Summary of CHI ’98, Atlanta, GA, pp. 1-2.

- LaBarbara, J. 1977 ‘Max Neuhaus: New Sounds in Natural Settings’, Musical America, October.

- LaBelle, B. 2002, ‘Causing effects: Between Sound and its Source’, Earshot, vol. 3, pp. 8-9.

- Leach, N. 2002, ‘Forget Heidegger’, in Designing for a Digital World, ed. N. Leach, Wiley Academy, West Sussex.

- Lucier, A. 1990, ‘I am Sitting in a Room (1970), for voice and electromagnetic tape’, in I am Sitting in a Room, A. Lucier, Lovely Music, Ltd, New York.

- Martin, E. 1994, Architecture as a Translation of Music, Princeton Architectural Press, New York.

- Neuhaus, M. 1994, Sound Works: Volume I – Inscription, Cantz, Ostfildern-Stuttgart.

- Neuhaus, M. 1995, Evocare L’Udibile, Charta, Milan.

- NOX (2004), ‘Son-O-House’, Available at: http://www.evdh.net/sonohouse/nox.html

- Puglisi, L. P. 1999, Hyper Architecture: Spaces in the Electronic Age, Birkhauser, Basel, Switzerland.

- Rasmussen, S. E. 1959, Experiencing Architecture, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

- Reed, V. 2000, ‘Living Out Loud’, Soundscape: Journal of Acoustic Ecology, vol. 1, no. 2, pp.22-23.

- Rudi, J. 2005, ‘‘From a Musical Point of View, the World is Musical at any Given Moment’: an Interview with Bill Fontana’, Organized Sound, vol. 10, no.2, pp. 97-101.

- Rushkoff, D. 2002, ‘The Digital Renaissance’, in Designing for a Digital World, ed. N. Leach, Wiley Academy, West Sussex, p. 16-20.

- Scott, R. 2004 ‘Surface Architecture’, in Earshot vol. 4, pp. 13-16.

- Tak, W. 1958, ‘The ‘Electronic Poem’, performed in the Phillips Pavilion at the 1958 Brussels World Fair: The Sound Effects’, Phillips Pavilion Technical Review, no. 20, pp. 43-44.

- Thompson, E. 2004, Wiring the World: Acoustical Engineers and the Empire of Sound in the Motion Picture Industry, 1927-1930, in Hearing Cultures. Essays on Sound, Listening and Modernity, Veit Erlmann (ed.), Berg Publishers.

- van der Heide, Edwin (2004), ‘The Composition of the Sound Environment for the Son-O-House’, Available at: http://www.evdh.net/sonohouse/evdh.html

- Varese, E. 2004, ‘The Liberation of Sound’, in Audio Culture. Readings in Modern Music, eds. C. Cox & D. Warner, The Continuum International Publishing Group, New York, p. 17-21.

- Wassermann, K. C., Manzolli, J., Eng, K. & Verschure, P. F. M. J. 2003, ‘Live Soundscape Composition based on Synthetic Emotions’, IEEE Multimedia, vol. 10, pp. 82-90.