Objects of Affect: the Domestication of Ubiquity

Publication: Technoetic Arts: A Journal of Speculative Research, Volume 11 Number 3, © 2013 Intellect Ltd Article. doi: 10.1386/tear.11.3.307_1

Keywords: domestication, architecture, inhabitancy, IoT, sensors, ubiquity

Abstract

This article contextualizes digital practices within architectural spaces, and explores the opportunities of experiencing and perceiving domestic environments with the use of media and computing technologies. It suggests methods for the design of reflexive and intimate interiors that provide informational, communicational, affective, emotional and supportive properties according to embedded sensorial interfaces and processing systems. To properly investigate these concepts, a fundamental criterion is magnified and dissected: dwelling, as an important ingredient in this relationship entails the magical power to merge physical environment with the psyche of inhabitants. For this reason, a number of views are presented and discussed, providing necessary conditions to include matters of affectivity, ubiquity and layering complexity of interior space. Moreover, specific processes of the possibilities of the digital are mentioned, and examples are presented of the infusion and diffusion of ubiquitous computing technologies within domestic spaces. To briefly conclude, this article is an attempt to discuss the relationship of human-architecture-computer symbiosis and the design process of creative and innovative spaces that affect states of memory, perception, experience, as well as mood and emotion.

Shaping Intimacy

Mid Pleasures and palaces though I may roam, Be it ever so humble, there’s no place like home; A charm from the sky seems to hallow us there, Which, seek thro’ the world, is ne’er met with elsewhere. Home. (Payne 1880)

Domestic architecture is a form of architectural design that relates to the creation of intimate and isolated spaces of everyday life; i.e. houses, homes, sheds. An important aspect for their development is to consider a number of parameters such as aesthetics, practicality, daily interactions, safety, and security, to name a few. As Rasmussen agrees, this becomes a ‘very special functional art’, confining ‘space so we can dwell in it’, able to shape a fundamental ‘framework around our lives’ (Rasmussen 1959: 10). This framework is an essential element in the personal growth of the person that lives within this space, having powerful connections to the mind and soul, establishing strong psychological and emotional connections between inhabitants and the space itself; as Martin Heidegger argues, this is the only possible way for dwelling to occur:

These buildings house man. He inhabits them and yet does not dwell in 18. them. In today’s housing shortage even this much is reassuring and to 19. the good: residential buildings do indeed provide shelter; today’s houses 20. may even be well planned, easy to keep, attractively cheap, open to air, 21. light and sun, but do the houses in themselves hold any guarantee that 22. dwelling occurs in them? (Heidegger 1971: 145-46)

According to Heidegger, no matter how sophisticated or skillfully designed a house may be, it does not necessarily become a home, or that dwelling is automatically established beforehand. An accumulative process of domestic time and experience builds hidden layers of meaning, affection and emotion between space and inhabitant. The architectural ‘object’ becomes an extension of a man’s personality and psyche, providing as an exchange not only survival possibilities, but also poetic and colourful properties, defining new force fields in the perceptual universe: ‘cellar and attic can be detectors of imagined miseries, of those miseries which often, for all of life, leave their mark on the unconscious’ (Bachelard 2006: 74). Therefore, a necessity is established to closely observe how these captured instances of affectivity and emotional insecurities deeply infiltrate into the mind of the dweller – and vice versa.

One example that makes an attempt to approach this issue is Merzbau, an installation created in the 1920s by Kurt Schwitters in his own home, suggesting answers and questions on intimacy and personalization. Three-dimensional structures run free in space and sometimes transcend it, ‘cutting through the ceiling and floor to original armature of the building’ (Mansoor 2002) with countless nooks and grottos filled with objects of daily use – combs, pencils, notes. Thus, architectural space becomes an extension of the inhabitant, absorbing preferences, customs and rituals, and as S. Brand suggests, the ‘unchanging deep structure’ never remains unchanged, as it is building and rebuilding according to the actions of the inhabitants (Brand 1994: 11).

Architecture and inhabitants share a unique relationship of subtle communication and mutual affect. This coexistence defines also fundamental properties of their physical being: closed spaces with no fresh air will introduce mould to the walls, as well as affect the health of the person too (causing depression, fatigue, or even respiratory dysfunction). Consequently, this relationship needs to exhibit sensuous conditions and sympathetic properties to suggest symbiotic mutualism and promote a sustainable solution for future prosperity. Accurate personalization of the environment needs to be implemented and adjusted towards the expressional and creative domain of its occupants, and as A. Sharr argues the residence ‘should be understood through tactile and imaginative experience; not as a detached object’ (Sharr 2007: 46). A related premise by Rasmussen also suggests that architecture needs to be experienced and closely observed for its functions and properties, and more importantly to ‘dwell in the rooms, feel how they close about you, observe how you are naturally led from one to the other’ (Rasmussen 1959: 16). This exploration of the physical structure may indicate hidden layers of systems, meanings and secrets.

Ubiquitous Layering

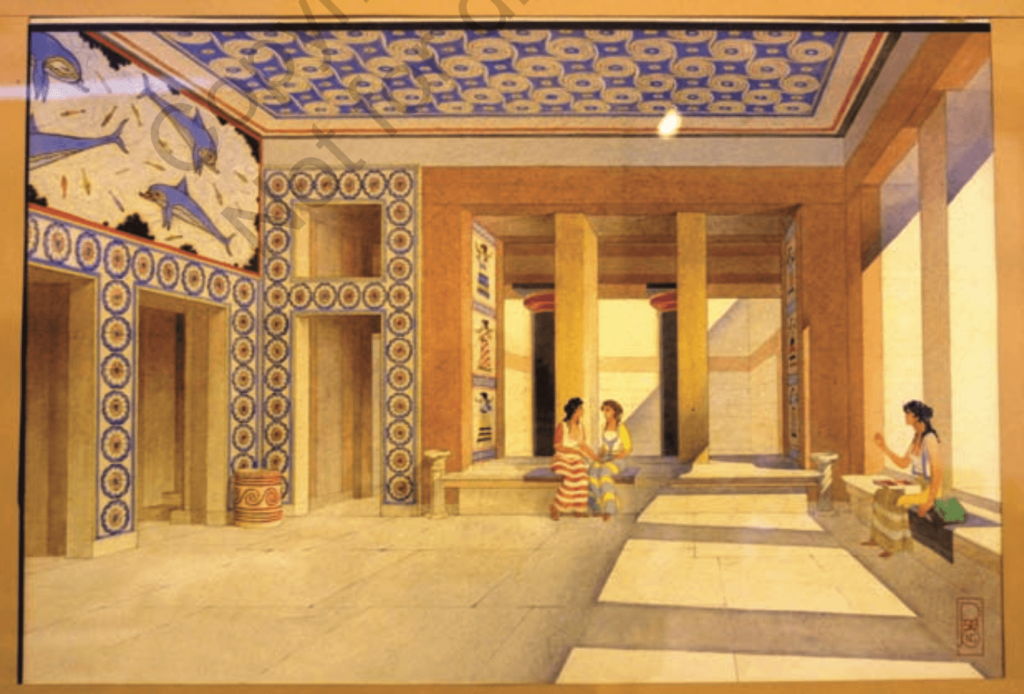

Spatial arrangement and manipulation of interior elements has been one kind of intriguing and demanding process especially during the past couple of centuries. Ubiquity has always been an integral part of architecture itself. Architects and designers depend on hidden layers of meaning and functions, trying meanwhile to show an aesthetically pleasing environment to its inhabitants. For example, plumbing is a functional and vital part for every house, nevertheless the mechanics of the system are always hidden and out of sight. In buildings built before modern amenities the retrofitting of pipes and wires requires a surgical insertion and invisible mending to leave no scars. Even from ancient architecture in the Palace of Knossos during the 18th century bc there is evidence that shows that the architectural design was a complex matter of decisions for balancing aesthetics, functionality and well-being. Through openings and passages sunlight is able to reach even the lowest parts of the Palace, ventilation and water management solutions run throughout the structure, however frescoes and paintings are present everywhere as the top layer of aesthetically pleasing interiors. Additionally, the design of the room affects a higher state of consciousness, symbolizing the ‘soul’s liberation from the earthly body’ (Castleden 1990: 92), providing sanctuary and spiritual amplification services.

Examining layers across time and place we may find different meanings of domesticity and inhabitancy, however, in every epoch the main desire is to enhance living experience, and provide necessary means to accomplish coexistence between people and space. Nowadays modern domestic architecture considers yet more layers for the construction of a house – seismic protection materials, sound and heating absorption and insulation, electricity, 8. telecommunications, to name a few. Computing devices and sensor technologies are seeping into the fabric to become another layer in the architectural design process, offering cyberdomesticity with complex sensor networks and context aware processing. If current lifestyle demands accurate personalization, instant adaptability, flexibility and significant results, inevitably ‘we must consider technological prosthetics’ (Spiller 1998: 32).

As currently we are entering into the third wave of computing, computational units and devices become diffused within interior spaces; M. Weiser’s vision will eventually come true: ‘the most profound technologies are those that disappear. They weave themselves into the fabric of everyday life until they are indistinguishable from it’ (1991: 94). Accordingly, a fundamental consideration is to scatter interfaces as transparent items onto the surfaces of daily use and to ‘concentrate on human-to-human interfaces and less to human-to-computer ones’ (Weiser et al. 1999: 693). Technology will then calm down and fade out into the background; transforming into a silent servant that takes care of a range of possible activities from hard labour to delicate and personal matters.

Absorbing the Digital

Licklider, Doug Engelbart, Ivan Sutherland, and other pioneers of interactive computing mostly had dialogue with desktop workstations in mind, whereas I now interact with sensate, intelligent, interconnected devices scattered throughout my environment. (Mitchell 2003: 159)

A vision of the future we already live in is for computational systems to become standard architectural materials establishing themselves as ubiquitous layers in physical and mental processes. This will eventually bring a new era in post-digital architecture where ubicomp and ambient intelligence dominate over spatial arrangement and design methodology, ‘just as system supersedes structure’ (Ascott 1996: 489). Nonetheless, this transformation poses significant confrontations to inhabitants, morphing awareness and perception, or altering current perspectives; as M. Goulthorpe notes ‘technology as extensions of man (in Marshall McLuhan’s terms) is never a simple external prosthesis, but actively infiltrates the human organism, certainly in a cognitive sense’ (Goulthorpe 2008: 38). In the short story collection Vermilion Sands, J. G. Ballard (2001) reveals the concept of the psychotropic house; the house of a future time where technology infiltrates into the architectural structure transforming them into kinetic forms with animalistic behaviours. In one passage, the main character mentions the following:

Many medium-priced PT homes resonate with the bygone laughter of happy families, the relaxed harmony of a successful marriage […] a really well-integrated house with a healthy set of reflexes – say, those of a prosperous bank president and his devoted spouse – would go a long way towards healing the rifts between us. (Ballard 2001: 190)

The psychotropic house seems to radiate specific stimuli that have been recorded on previous occasions, and more specifically in instances that the house ‘thought’ they seemed out of the ordinary (therefore important) based on sensorial input captured from inhabitants’ psycho-physiological responses. This computational process of media distribution in space has the authority to influence the poetic substance of the environment and consequently transform the inhabitants’ inner being into an analogous essence. This relates directly to an installation created by one of the authors (Stavros Didakis) that brings aspects of memory, experience and perception within space. Plinthos Pavilion consists of an architectural semi-transparent structure that uses digital and electronic technology to attain shiftable properties according to human behaviour. In this case, ubiquitous computing defines a dynamic immersion of light and sound that communicates affective properties to the visitors, creating transformable characteristics based on sensed interactions. Except of its ‘short-term understanding of the spatial activity, Plinthos has long-term, and more specifically episodic memory […] referring to recollections of its genesis’ (Didakis 2012: 312), however, instead of automatically triggered as in the case of Ballard’s psychotropic house, in this case memories remain hidden, unless visitors activate them using stem light devices that appear in the middle of the room. Upon triggering, ‘sonic events are distributed in the environment showing past snapshots of the structure’s embryotic state’ (Didakis 2012: 312).

Additionally, symptoms of the psychotropic house are evident in i-DAT’s Arch-OS.com project as well. Both as a manifestation of an intelligent and ubiquitous architectural virus, but also as a place for capturing the traces of human activity. Contrary to normal trends in the design of ‘Intelligent Building Systems’, Arch-OS attempts to transfer ‘intelligence’ from the building to the inhabitant. By making the impact of human activity tangible, inhabitants can then take a more informed responsibility for their actions. Here, the psychotropic qualities are manifested as a ‘Psychometric Architecture’:

The concept of objects (or places) seeming to record events and then play them back for sensitive people is generally referred to as psychometry. The objects can be called psychometric objects or token objects. (Morris 1986)

The introduction of monitoring technologies into the fabric of a building manifest the attributes of parapsychology in a ‘Psychometric Architecture’ (Phillips 2001), a paranormal possession of a building that replayed at night the activities that took place during the day, a kind of dreaming architecture. Within the domestic context the Arch-OS system may need an iteration or upgrade to Domest-OS, an Operating System that can cope with the familial activities of home sweet home, recording not just the tranquil moments but also embracing the tantrums, domestic violence and abuse hidden behind the twitching curtains. ‘Arch-OS-style polling of foot traffic and social interactions, coupled to output in the form of structural changes can take us in some genuinely novel directions’ (Greenfield 2006: 62). Or more pragmatic applications such as the exploration of energy visualization for carbon reduction in domestic environments for the EPSRC eViz project (http://www.eviz.org.uk/) (Figure 3).

According to these examples, we witness the gradual extinction of previous methods of interfacing with the architectural space. Technological penetration infects normal daily life with trends, keywords, protocols or issues of compatibility to gain access to the adornments of digital oases. A new cartography of living experience should be established in order to minimize confusion, disarranged traditions, misfits and failed control. Due to the reason that domestication becomes a matter of interface design, usability and user experience, interactive and technological artefacts need to establish their identity and their processing characteristics within the practical and emotional choreography that is composed in a daily basis and find their place in the routine of the household as functional embedded entities.

An important criterion for the infusion of digital into the physical and structural domain becomes the accurate contextualization of ubicomp domestication. As previously mentioned, the fragile and delicate domestic environment needs to be tenderly studied for its affective properties that are shaped according to inhabitants’ behaviour, social and economic status, family relations, mood, and overwhelming emotions. Thus, it is critical to realize ‘the need to understand the household in all its structured complexity’, and also ‘the need to understand the household as an element of the wider environment’ (Silverstone and Hirsch 1994), so that technological proliferation within domestic premises may be of any useful practice.

Objects of Affective Interiors

We do amazing things with technology, and we’re filling the world with amazing systems and devices; but we find it hard to explain what this new stuff is for, or what value it adds to our lives […] When it comes to innovation, we are looking down the wrong end of the telescope; away from people, toward technology. Industry suffers from a kind of global autism. Autism, as you may know, is a psychological disorder that is characterized by detachment from other human beings. (Chapman 2005: 23)

Indeed, as Chapman discusses in the above quotation, technology has to properly fit the home environment and needs to be tamed and disciplined, vis à-vis domesticated, and infiltrate actively into the living matter of a home’s existence providing information, meaning, connectivity, participation, to name a few. However, this new meaning ‘extends and transforms the boundaries around the home […] and can threaten to shift or undermine what is taken for granted in the routines of domestic life’ (Silverstone and Hirsch 1994: 20). Therefore, ubiquitous computing should not only fit within daily routines and activities or to provide necessary automations, but to become a part of the inhabitants’ life. And as in the case of a new member (pet, baby, tenant) that joins a home, significant changes in the daily routine start to emerge. Although, transitions sometimes are difficult and for some people takes a while to adjust, soon new experiences accumulate to the affective layers of the environment, building an array of memory cells that could never have occurred alternatively, giving the essential meaning of coexistence in personal and intimate spaces. In the same sense, technological penetration transmutes into a domestic object and it is valued for its dynamic and reflexive processes as well as the beauty and well-being it may offer, as shown in Csikszentmihalyi & Rochberg-Halton 1981.

Form, style and system architectural complexity vary enormously from one case to the other, nevertheless in most applications small sensorial and processing interfaces with low-intelligence and fairly easy complexity link with other instances creating a convoluted network of information and communication exchange and interaction, a scenario that has been coined the term ‘Internet of Things’ (IoT). The collaborative machine processing has a number of goals to accomplish until recently unachievable or limited to a certain extent. In this particular context, the ubiquitous object has to concentrate on affective properties of the inhabitant’s personal environment, and to embody functionality that is able to communicate in multiple levels, from emotional space to radical and eccentric behaviour.

Moreover, the contextualization of domestic ubiquity, the ‘object’, needs to consider cultural roles, aesthetics of use, psychosocial narratives and mostly explore its poetic sides rather than other related technicalities, as already suggested by Anthony Dunne (1999). Therefore, a number of qualities need to be employed into this adaptive and affective system that may include anticipation, playability, relevance, parafunctionality, immersion, control/autonomy, and personal connectedness, to name a few (Fishwick 2006: 385). Even though these properties increase the complexity of the development, ‘the solution is to understand the total system, to design it in a way that allows all the pieces fit nicely together’, so that its usage and performance is optimal (Norman 2011: 46).

Domestic architects normally design spaces to a certain extent, always leaving room for the owners to fit and adjust their personal preferences. Interior elements, furniture, colours and other necessary embellishments are choices that properly define the personalization of the space. In the same sense, ubicomp functionality needs to be programmed to a certain extent as well, and provide possibilities for the user to explore, discover, and change according to their own aesthetics, lifestyle and activities. According to this, ambiguous programmatic elements may provide unimagined outcomes and open up unexplored possibilities of noisy randomness suggesting an organic behaviour that a person could more easily relate to.

Additionally, to supply adaptive performance the system has to automatically reconfigure based on emotional, sensorial and physiological properties, ensuring continuous evolution and mutual growth so that it can reach a higher level of empathy. This achievement is accomplished ‘far beyond the ephemeral world of technocentric design’ where one is able to find ‘a rich and interactive domain founded on [this] profound human need’ (Chapman 37. 2005: 18). Therefore, it is important to closely investigate and experiment these practices of ubicomp based on the aforementioned criteria and identify the alchemic ingredients to truly suggest affectivity, empathy and accurate personalization, mainly because if we want ‘to understand the transforming potential of a particular line of technological development, it is necessary to know the range of its possible applications’ (Gershuny 1994: 231). 43.

Conclusion

The domestication of technological artefacts has always been a topic for discussion, merely to quantify and qualify the possibilities in each instance, but primarily to explore human nature and to better understand perception, memory, experience, affectivity and well-being. Unquestionably digital technology at present exists as an element that covers and executes a wide range of activities – from calculating numbers and symbols, to sense and adjust innermost feelings. The co-dependence between human and the machine continues to grow, defining even more areas of communication and interaction. As such, the home environment has to be properly set up to correctly represent this relationship in all of its manifestations, and to avoid poisoning the human mind with unnecessary / saturated information or redundant functions that over-complicate daily activities.

Another issue for reflection and consideration is the identification of complex, often contradictory and culturally located methods for approaching and developing ubiquitous computing applications within domestic spaces. State of the art technologies and the latest hardware and software tools need to be disguised into daily objects or as routinized activities that play an empathetic role inside the family environment, and adapt to current conditions of idiosyncratic and unpredictable actions and reactions. Therefore, this becomes not only a question of how to embed and use the technologies, but also how domestic life functions in general.

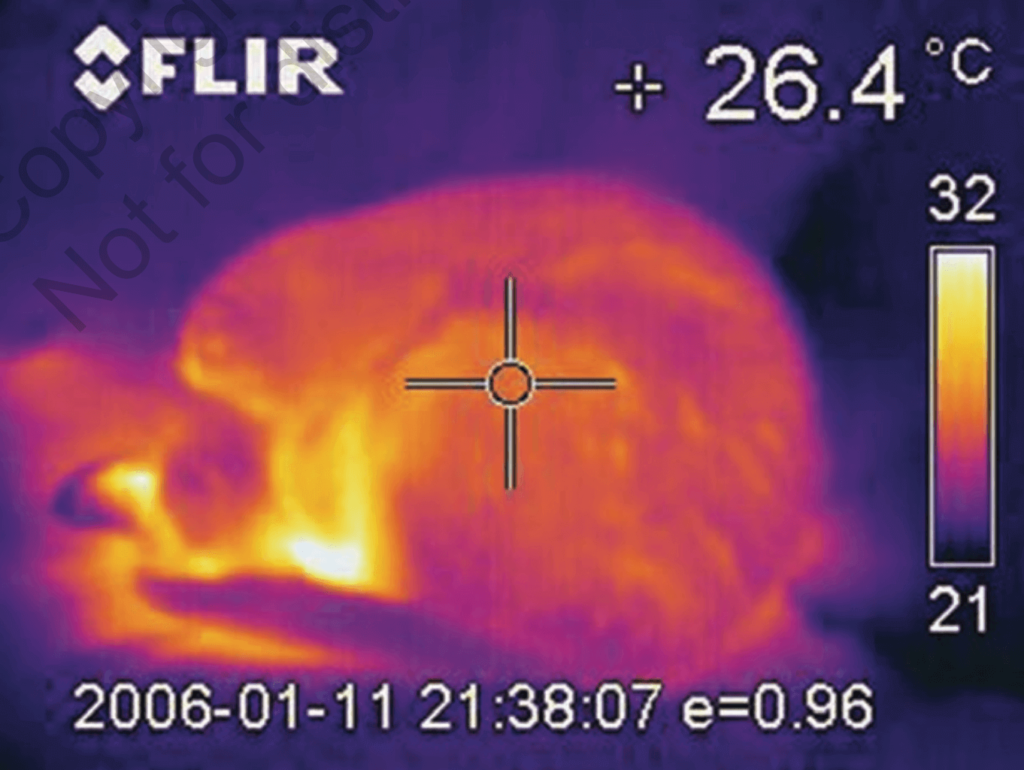

To accomplish a case where the environment is able to ‘sense’ fluctuations in mood, behaviour or perception, computational processes have to constantly monitor a number of physical variables of a person’s environment and algorithmically calculate the necessary conditions for interacting appropriately. It is not only about how and what to understand from the received sensorial information, but also how to use it in real and random conditions that constitutes empathetic and intelligent. If this ever becomes the case, then ubicomp will be able to connect to deeper and more meaningful levels of communication with the inhabitants, creating acceptance, trust and domestication.

Studying the domestication of ubiquity, significant challenges, risks and opportunities are presented. Popular myth would lead us to believe that every technological innovation becomes a medium of expression, creativity and experimentation, swiftly followed by the optimism of bringing well-being or a better sustainable future. Fitting snuggly into a domain popularly termed the ‘Internet of Things’ (IoT), these ‘enhanced’ environments present a new hierarchy of ‘thingness’; the body as ‘thing’, the building as ‘thing’ and the environment as ‘thing’. Rich interactions across these forms located in this new territory afford provocative and controversial ways of hybridization and technological proliferation.

References

- Ascott, R. (1996), ‘Behaviourables and Futuribles’, in K. Stiles and P. H. Selz (eds), Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art: A Sourcebook of Artists’ Writings, California: University of California Press, pp. 489–91.

- Bachelard, G. (2006), ‘The oneiric house’, in B. M. Lane (ed.), Housing and Dwelling: A Reader on Modern Domestic Architecture, New York: Routledge, pp. 74–77.

- Ballard, J. G. (1962), ‘One Thousand Dreams of Stellavista’, in Ballard, J. G. and Amis, M. (eds.) (2009), The Complete Stories of J. G. Ballard, New York: W. W. Norton & Company Inc, pp. 305–320.

- Brand, S. (1994), How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They’re Built, New York: Viking Penguin.

- Castleden, R. (1990), The Knossos Labyrinth: A New View of the ‘Palace of Minos’ at Knossos, London and New York: Routledge.

- Chapman, J. (2005), Emotionally Durable Design: Objects, Experiences and Empathy, London: Earthscan LLC.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. and Rochberg-Halton, E. (1981), The Meaning of Things: Domestic Symbols and the Self, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Didakis, S. (2012), ‘The Myth of Symbiosis, Psychotropy, and Transparency withing the Built Environment’, Technoetic Arts: A Journal of Speculative Research, 9: 2+3, pp. 307–13.

- Dunne, A. (1999), Hertzian tales: Electronic Products, Aesthetic Experience and Critical Design, London: RCA CRD Research Publications.

- Fishwick, P. A. (2006), Aesthetic Computing, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Gershuny, J. (1994), ‘Postscript: Revolutionary Technologies and Technological Revolutions’, in R. Silverstone, and E. Hirsch (eds), Consuming Technologies: Media and Information in Domestic Spaces, New ed., London: 12. Routledge.

- Goulthorpe, M. (2008), The Possibility of (an) Architecture: Collected Essays by Mark Goulthorpe, dECOi Architects, New York: Routledge.

- Gustafson, H. (2009), ‘An Artistic Recreation of the Queen’s Apartments’, http://hgustafs.myweb.usf.edu/cre117.jpg. Accessed 20 February 2013.

- Greenfield, A. (2006), Everyware. The Dawning of the Age of Ubiquitous Computing, Berkley: New Riders, pp. 62.

- Heidegger, M. (1971), Poetry, Language, Thought, New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

- Mansoor, J. (2002), ‘Kurt Schwitters’ Merzbau: The Desiring House’, Invisible Culture – An Electronic Journal for Visual Culture, Issue 4, http://www.rochester.edu/in_visible_culture/Issue4-IVC/Mansoor.html. Accessed 12 February 2012.

- Mitchell, W. J. (2003), Me++ : The Cyborg Self and the Networked City, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Morris, R. (1986), Letter to the Artist (Koestler Chair of Parapsychology at the University of Edinburgh 1985 to 2004), 21 October.

- Norman, D. A. (2011), Living with Complexity, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Payne, J. H. (1880), Home Sweet Home, Boston: Lee and Shepard. - Phillips, M. (2001), ‘Psychometric Architecture’, in S. Speed and G. Grinstead 31. (ed.) V01D, Exhibition Catalogue, Plymouth: i-DAT, Plymouth Arts Centre, limbomedia and Digital Skin, pp. 52–56.

- Rasmussen, S. E. (1959), Experiencing Architecture (trans. Eve Wendt), 1st United States ed., Cambridge, MA: Technology Press of Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Sharr, A. (2007), Heidegger for Architects, Thinkers for Architects, London and New York: Routledge.

- Silverstone, R. and Hirsch, E. (1994), Consuming Technologies: Media and Information in Domestic Spaces, New ed., London: Routledge.

- Spiller, N. (1998), Digital Dreams: Architecture and the New Alchemic Technologies, London: Ellipsis.

- Weiser, M. (1991), ‘The Computer for the 21st Century’, Scientific American, 265: 3, pp. 94–104.

- Weiser, M., Gold, R. and Brown, J. S. (1999), ‘The Origins of Ubiquitous Computing Research at PARC in the Late 1980s’, IBM Systems Journal, 38: 4, pp. 693–96.

Suggested Citation

Phillips, M. and Didakis, S. (2013), ‘Objects of affect: The Domestication of Ubiquity’, Technoetic Arts: A Journal of Speculative Research 11: 3, pp. 307–317, doi: 10.1386/tear.11.3.307_1.